100 Favorite Video Games

|

| Bill |

| [email protected] AIM: Basher Lemming |

First, a disclaimer. The order of this list isn't definitive, and could change whenever I damn well please. More importantly: I am one of those "games as art" fags your mother warned you about and I'm not ashamed to admit it. Not that I didn't play Super Mario World or other of the more obvious classics, or that I don't appreciate blowing things up for the sake of blowing things up. But when I think about the games that really stick out in my memory, the ones that really left an impression, these are the ones that come to mind. The oddities. The ones that did something new and different and did it really well. So don't write to me, personally offended that I think Little Nemo is a better game than Doom or something. I don't, necessarily. These are just the 20 games that have endeared themselves the most to me.

20. Little Nemo the Dream Master (NES, 1990)

When I was young, having a relatively large sum of money was a pretty big deal. Most importantly, it meant I could go buy a game. I didn't always have a specific game that I was interested in getting, mind you, but that didn't matter. I finally had the money, dammit, and that meant I was getting something. Sometimes this way of thinking had tragic results. But sometimes, it led to games I never would have considered otherwise.

Little Nemo is not a great platformer. The whole animal transformation gimmick -- you feed an animal some candy, you get to make use of his powers -- is sorta neat, but aside from maybe the bee, they all control as bad as Nemo does. None of them can actually jump high enough to get over the enemies you have no other way of avoiding, and each hit knocks you back 20 feet which, more often than not, lands you in more trouble. But I've always had an affection for the game that I can only attribute to the use of its source material. As will become painfully evident in reading this list, I'm fond of games that skew outside the mainstream and have a style all their own, and basing a game on a comic from 1905 is pretty damn skewed. They didn't try to change it much, either; from the introduction with its surreal calliope/accordion theme to the characters that introduce each stage (who admittedly serve no purpose other than to be cameos that no one playing the game will recognize anyway) to the stages themselves, ranging from a forest of mushrooms to a ride on a giant toy train to a house flipped upside down.

Capcom made a different (i.e. not a port) Nemo game for the arcades, and come to think of it, the 1992 Little Nemo movie was also produced in Japan. What is it about this comic that appeals to them so much?

19. Wipeout (PSX, 1995)

Speaking of style. The Playstation oozed it, and not a superficial "it's cool cuz we scream and that's cool so buy our cool game" attitude like that which Sega used to chip away at Nintendo a few years prior. This was style that was actually rooted in some sort of artistic direction. Whether by Sony's urging or just by the changing tides of the industry, around the 32-bit era games started separating themselves from each other, becoming increasingly unique in design so that even two games of a similar type in a similar genre could be very different. Wipeout excelled in this regard by employing the services of The Designers Republic to create the fonts, logos, menus.. pretty much everything that influenced the look of the game. It seems like such a little thing, to have professionally designed corporate logos for each vehicle manufacturer, and yet it adds substantially to the atmosphere of the game. Packing the soundtrack with the likes of the Dust Brothers and Prodigy helped too.

Later, the Designers Republic pitched in again with Wipeout XL (Wipeout 2097 in Europe; you know we Americans can't handle numbers) and Wip3out (either of which could be put in this spot, really, but I like to stick with the originators), but after that they moved on to other things. It's never been fully explained why, though part of it may be that the "club kid" culture that the series catered to had moved on, or at least changed quite a bit from when the series debuted in 1995. You certainly weren't seeing the likes of Firestarter on TRL anymore. So instead, the more recent games have used various companies just trying to be tDR, meaning you get stuff like the interface for Wipeout Pure, which looks like a control panel for those robots in Bjork's All Is Full Of Love video.

Unlike Nemo, however, there actually was a very good game underneath the wrapping. It was fast, it had a weapon system that added a new layer of strategy to the gameplay, and the physics of an anti-gravity vehicle made for a completely different experience than anything that had come before. Floating cars in previous games like F-Zero were little more than a gimmick (they basically drove like normal cars on ice), but here you had to adjust to a totally different style of driving. No tires are going to help you skid into that turn; you have to learn to sling your weight around it. You aren't going to crash into that bank, you're going to slide up it sideways like Marty in the tunnel with Biff in Back to the Future II. Inertia is always a factor in driving, but with nothing holding you to the track it became the most important factor. It was sort of half way between trying to fly a plane and drive a car, and thankfully that happened to be a pretty fun way to race.

18. Food Fight (Atari 7800, 1987)

When trying to think of a good representation of the old school on this list, there were a few candidates. There's Pac Man and Frogger and Galaga and all that, of course, but they're pretty played out (and were so even then). River Raid came close, but the repetition and limited changes (only occasionally did the path branch into two directions, and enemies always showed up in the same places and moved the same way) put it just behind my final choice, a game that most people have probably never played.

The concept is pretty simple. You control Charlie. Charlie has a giant head and an insatiable love of ice cream cones, perhaps because they cool the heat generated by his giant head. Each stage has a cone on the other side of the screen, slowly melting and thus acting as a timer. You've got to get Charlie to the cone before it melts, but there are angry chefs scattered throughout the stage between him and the cone, determined to stop him because his giant head blocks out the sun and keeps them from getting sexy tans. Or something.

There are also piles of food of varying types scattered around, and that's where things get interesting. Charlie has no defenses of his own, but he can run over to a pile, pick up a handful of food, and chuck it in any direction. He can take out the chefs this way, so the game becomes a matter of running from pile to pile, keeping the chefs at bay and working your way to the other side of the room. This was the first game I ever played (and has to be one of the first games period) to have a instant replay feature, and it deserved it. There was nothing cooler than getting cornered by several chefs, making a last second break for it between two of them, and having them nipping at your heels just as you reach a pile of tomatoes, whip around, and blast the shit out of your aggressors with firey (or at least room temperature) fruit of vengeance. Then getting to see it all again because the computer decided you had done a pretty good job (and it was hard machine to impress, too). The piles had limited supplies, which only increased the tension, with the exception of watermelons. For some reason watermelons never ran out of ammo, but only appeared every few stages, so it was a nice stress reliever after a couple of close calls to get to a melon and go all Rambo With Fruit And A Big Head on all comers until you had to go grab the cone right before it finished melting.

There's a lot to be said for dynamic content. Though the gameplay was very basic, the position of the piles and the chefs and the holes in the floor changing each time was enough to provide almost limitless entertainment. For all my talk of artistry and design, the most important piece of the puzzle is still a solid, fun gameplay mechanic.

17. Lemmings (SNES, 1991)

There's a certain type of game I've always liked that I've had a hard time putting in a particular category. Lemmings is one. Sim City is one. Roller Coaster Tycoon is one. The Incredible Machine is one. The best description I've come up with for them is "sit down and work" games, because that's the general idea they share -- you're presented with a playing field, a box of pieces to work with, and then you just sit down and figure out how to put it all together. Research should be done on how many Lemmings players also do jigsaw puzzles.

Sit down and work games were a popular genre at one point in the PC's lifespan, and Lemmings was one of the best. Puzzles that were challenging, but not impossible, with multiple solutions (frenetic building could occasionally cheat your way out of bad spots), and a lot of them to keep you busy. All wrapped up in a charming little package.

If I may go on a tangent for a moment (why stop now), Lemmings is an interesting example of the market atmosphere in the old days. Here we have what could not be a clearer case for family entertainment: a easy to learn puzzle game featuring cute little fuzzy creatures. And yet the original DOS version of the game contained several references to heaven and hell, levels built out of bones, skulls and bloody viscera, traps that ripped lemmings apart, and a level requiring your lemmings to traverse a large stone 666. These days such things wouldn't even be considered, because they could up your ESRB rating and needlessly cut into the number of people willing to buy your game. But at the time, it was simply assumed that PC games would be purchased and played by an adult. There's lots of talk now about games for mature audiences, but these games have to be designed with that mature market in mind. Truly "mature" games shouldn't have to have any consideration for the market at all. They just are what they are. Unfortunately, that's more or less impossible anymore.

As you can imagine, the religious bits were taken out of the SNES version. The levels made out of guts were left in. Insert appropriate social commentary here.

16. Jumping Flash! (PSX, 1995)

You've got to put the exclamation point in there. One, because it's in the title, and two, because you can't help but think of it that way after you've heard the title card announcer.

So the Playstation has been out a few months, and my friends are talking about all the cool games they've played on it. I've got to get in on this action, but I don't have the money to buy a system. I head out to my local Blockbuster and rent one and a couple games, and report back in gym class the following Monday.

"Hey, I rented a Playstation over the weekend!"

"Cool. Did you get Wipeout with it?"

"Yeah, it's really awesome!"

"Did you get Resident Evil?"

"No, I got a game where you hop around in a giant robot bunny!"

Middle school was tough.

It's a better concept than it sounds, honest. Each level is a collection of floating chunks of earth and various structures, and hidden around the level are four jetpods. Robbit, the robot bunny (presumably the brother of Rabbot from ATHF) has to hop around and collect these pods to move on to the next level. He can shoot lasers, for what that's worth, but his main feature is the ability to leap 50 feet in the air, then jump again in mid air, then jump again after that. So the whole game is basically an acrophobe's nightmare as you jump from one platform to the next, climbing hundreds of feet into the air, your view (from Robbit's perspective, no less) helpfully shifting downwards when doublejumping to the spinning and ever-diminishing speck of ground below so you can properly know when it's time to hurl.

The jetpods aren't too hard to find, and the enemies are little more than a nuisance. The fun of the game just comes from playing around, making huge leaps across the stage, cutting your own path across the tops of skyscrapers (and pushing a little too far to see if you can juuuust reach that last one way out there..), finding your way to the highest point you can manage, then leaping off and enjoying the freefall before landing, unharmed, at the bottom again. Unintentional falls are not always quite so fun, as most of the platforms stretch out over empty sky which means death for a mistimed jump.

Jumping Flash! 2 was just as good if not better, and I consider them both to share this spot. Now, speaking of fabulous flying machines..

15. Pilotwings 64 (N64, 1996)

I suppose it's appropriate that these two are together, because they're both about the enjoyment of free flight -- not flying to go shoot something, or do stunts, but just doing it to glide through the air and watch the world pass beneath you. Pilotwings 64 was a better realization of what the original Pilotwings wanted to be; I loved the original, but there's only so much you can do with Mode 7. Whether you were sky diving or hang gliding or rocketpacking, you were still doing it in a big empty room with a picture of a runway and some grass on the floor. Here they could finally have a real world with little details to fly around and examine, though technical limitations still crept in and kept the levels from being very big. The fun of flying a plane is lessened somewhat when the whole island you're on passes under you in a couple of seconds.

But there's another reason this game is here; It's one of the most relaxing titles ever made. I would've paid full price just for the birdman mode, which unfortunately does not involve defending Shaggy and Scooby against possession charges but does mean flying at your own pace with no limits on time or fuel through the stages you've unlocked while jazzy muzak on loan from the Weather Channel's Local On The 8s plays in the background. It's hard to stay stressed when you're drifting over an old castle under a full moon.

A new Pilotwings is currently being worked on by Factor 5, the Rogue Squadron/Leader/Strike guys, and provided it doesn't suck, it should hopefully allow for much larger environments, removing that last technological hurdle and possibly replacing this entry on this list.

14. Jetpack (MS-DOS, 1993)

Without money to buy games, I had to take whatever I could get. A couple of times, this meant one of those 5 dollar "500 games in one!" shareware discs they'd sell on corner racks at Office Depot. This was how I found and played most of the computer games of the early to mid '90s, but it had the added benefit of exposing me to a number of games I wouldn't have heard of otherwise. Games that were often constructed entirely -- music, sounds, graphics, coding -- by one person, and never found their way to any store shelves. Jetpack was such a game.

Essentially Lode Runner with a jetpack, the game involves collecting all the green gems in a level and then finding your way to the exit. To be honest, I never played the premade levels all that much. There were only 10 with the shareware demo, anyway, and I've never bothered to sit down with the full version. That was never the real draw, anyway. What made Jetpack so special was its level editor.

It was a combination of an editor that was extremely easy to use and gameplay that allowed for millions of possibilities. I spent several years making hundreds of levels; saving one, exiting the game, renaming the file (as the demo only allowed you to save a level as register.jet), then going back in and making another one. I made themes that spanned dozens of levels, like a continuous cave where the exit for one stage would be the entrance for the next. I was especially fond of long gaps over spike pits with only a scattering of small blocks covered in ice or conveyor ladders that pushed you down as means of getting across.

I wasn't alone, either. Hundreds of user-made levels, as well as the full version of the game can be downloaded for free from Adept Software's site.

13. The Fool's Errand (MS-DOS, 1989)

Try to follow me here. The Fool's Errand is a story, made up of dozens of chapters, only a few of which are available to you at the outset. In addition to telling another small part of the story, each chapter has a puzzle associated with it, that one must solve in order to open up another chapter. Solving puzzles also adds another piece to the map the Fool is given at the beginning of the game, but the pieces are not placed in any order. So you're hopping from one chapter to another, usually not in sequential order, solving puzzles and adding to your map, until finally the whole story is revealed to you. You only have one puzzle left, the first chapter, the one where you got the map to begin with.. And you realize the puzzle is to arrange all the pieces you've been given along the way, using clues hidden in the chapters that you may not have realized were even there. It's a meta-puzzle, to use the designer's term; a puzzle that uses other puzzles as its clues. Then when the map is assembled, it reveals 14 more puzzles to be completed to at last reach the finale.

I was not surprised to see that Cliff Johnson, the game's designer, has made a career out of building puzzles. In 2002, he was asked by David Blaine to construct a treasure hunt to win $100,000 that wasn't solved for 16 months. Unlike many games of this type that rely on slider puzzles and the same visual logic puzzles that you see over and over again (connect the sixteen dots using only six lines and so on), the bulk of the work in the Fool's Errand are word games like cryptograms and crosswords, or a combination of visual and word games, like polyominoes with words printed on them. There are also occasional oddities, like a poker-esque game with Tarot cards that can only be won by learning which combinations of cards beat which. It's a great, challenging collection woven together in a unique and entertaining way.

Johnson has made the Fool's Errand free for download from his site for Windows, Mac or Amiga. For Windows you can either use the MS-DOS version or jump through 80 hoops to get a defunct Macintosh emulator to run the other version in Windows. Stick with the MS-DOS version. Just make sure you use Moslo with it, or certain parts will go too fast for you to play properly.

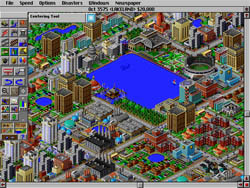

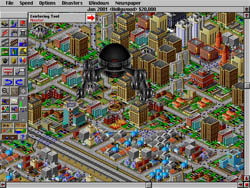

12. Sim City 2000 (MS-DOS, 1993)

My esteemed colleague Jon has chosen the original Sim City for his list, and I can't argue with that. It was one of the major deciding factors that caused me to pick a Super NES over a Genesis, and I played the hell out of it. However, while the original defined the series (and in many ways, the genre), and the latest Sim City 4 adds lots of great little details as well as some beautiful visuals, it was Sim City 2000 that really took a good idea that had been started in the first game and ran with it, revolutionizing it's predecessor while all sequels since have simply been natural evolutions.

It's another one of those sit down and work games, like Lemmings, but with the total freedom and openness that glued me to Jetpack's level editor for years. You can craft a complex city exactly as you wish, right down to each individual acre. Not that I ever had the patience or forethought for something like that. My cities were always sprawling, ugly things, a random assemblage of subdivisions and lots built at a moment to satisfy immediate needs without a lot of thought for the whole. Just like real cities. So who said games aren't educational.

In addition, SC2K introduced the idea of arcologies to me, and now I demand that I see one constructed and habitated before I die. Preferably a Darco.

11. Katamari Damacy (PS2, 2004)

Katamari drew a lot of comparisons to Jumping Flash! when it came out, and for good reason. They're both quirky, niche Japanese titles, but they also both eschew excessive challenge for simple, fun gameplay. The King of the Cosmos accidentally knocked the stars out of the sky, and thus the Prince must collect material to make new stars (like I said, quirky). Thus the only goal is to roll a sticky ball around the world, collecting the items that stick to it, gradually growing your ball as more (and larger) stuff sticks to it until it reaches the proper size. You can start out the size of a mouse, collecting thumbtacks and batteries and eventually grow until you're picking up fence posts and people and cars and buildings...

It's the purity of the experience that really sells the game. It's amusing (pretty much everything the King says is funny), the music is great, and the gameplay is simple. You just roll around and collect stuff, that's it. It's not very difficult, so there are no frustrations or bad spots or slow sections to distract you from just having fun with it. During the last level, I had one of those little moments where you step outside yourself for a moment and realize, "this is why I play video games." That's how unadulterated and sublime it is.

10. Ico (PS2, 2001)

There's one term to describe Ico, and that's absogoddamnedlutely gorgeous.

The developers were inspired by the impressionist style of painting while creating the look of the game, and if I knew more about art I would say something more about that. As I don't and don't wish to embarrass myself, I'll just say that light is used to great effect throughout the game, especially when stepping out of the dank, dark castle into the small outdoor areas, where the sunlight temporarily blinds you and the whole scene is overexposed, just as when going outside after a long time indoors in real life. Light is everywhere, in fact; it washes over outdoor scenes, it streams through windows, and even Yorda, the young girl Ico helps to escape the castle, radiates with an ethereal glow. Screenshots don't do the game justice; you really need to see in front of you and move around freely in it to appreciate it. There are times when you can stop and be almost certain an area is pre-rendered, but in fact everything is being done in real time.

But there's another aspect to Ico that makes it stand apart, and that's the relationship between the main character, Ico, and the girl who he finds in the castle, who he must lead to safety. The two don't even speak the same language, so there's little dialog and what there is you can't understand anyway. Yorda has been kept in a cage by the queen; she's scared and frail, so she can't wander around in the castle by herself. You must take her hand and lead her through the traps and puzzles strewn throughout the game, and not only does this work as a great puzzle mechanic (how am I going to make a path she can cross?), but also adds a surprising emotional attachment for the player. Having to guide this young girl every step of the way makes one truly care for her and her well-being, not just because you need her to continue on but because you really want to help her get out. And you can't help but grow fond of her when you let go of her hand to go check out a new area, only to look back later and see her gingerly stepping forward to explore the surroundings, stopping to examine a pond or a small bird hopping nearby.

It's sort of odd to compare Ico to the action hero killfest games with buxom vixens being rescued by steroid-pumped beefcakes wielding guns the size of God that we see so much of. Because, really, they're both a way of acting out the same basic male fantasy. But where the action games are the oppressive, dominating, gluttonous form of the fantasy that makes feminists' heads explode, Ico represents the pure, innocent essence of the idea. That down deep, behind all the posturing and macho bullshit, all men, since they were boys, just want to be the hero with the stick, swinging away at the monsters of the world to protect what they care about.

9. Final Fantasy Tactics (PSX, 1997)

I didn't really want to put this here, actually. I already have two Final Fantasies on this list, and a third just seemed too much. I could only justify it to myself by saying that this isn't really a "normal" Final Fantasy, and it also happens to be a superb game no matter what name is on it. Better than many of those "normal" FFs, in fact.

It's a marriage made in heaven. The job system from Final Fantasy V and a full fledged strategy game, allowing you to really get into each job and customize your team exactly the way you want, whether it be archers to attack from afar, knights and monks to pound the hell out of the enemy up close, or some of the stranger jobs in between, like calculators that attack based on numbers in characters' stats and geomancers whose attacks depend on the type of ground they're standing on at the time.

To be sure, the meat of the game had amazing depth to it (there are people who have sunk hundreds of hours into learning every skill in every job for every character), but what sealed the deal was a specialty of Square's: A great package. The graphics were very pretty for what amounted to a bunch of blocks with character sprites over top, and the story was engaging even after it completely lost me. But perhaps what I remember most about it is that FFT had what is, to this day, one of the most beautiful soundtracks ever made for a game. While many composers were still booping and beeping their way around, Hitoshi Sakimoto was using that same Playstation synth to create a epic orchestral score. Listen to some of the samples, especially Apoplexy, and wonder how some of those other composers even faced themselves in the morning.

8. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater (PS2, 2004)

I was never that big a fan of the MGS series. I got the first one after hearing over and over how great it was, and while I certainly enjoyed it, I still wasn't quite blown away. Then MGS2 came and there was quite a lot of blowing to be found. Much has been said about the ridiculous plot and the whiny Teen Beat coverboy you're forced to play as after the first hour, but to be honest, even if you had been Snake and the plot had been better, you would still be wandering around a boring-assed, prescription bottle-colored clean-up facility where every room looks the same for 10 hours and then it'd be over.

So I had little to no interest in MGS3. I was still going to play it, of course, just to see what they'd do with it if nothing else. But I held no hopes for it. Imagine my surprise, then, when I gradually realized as I progressed that I was playing the game of the year. On my list, anyway, it beat out GTA: San Andreas, which I had thought up to that point would have a lock. But MGS3 just got it right, in every conceivable way.

In gameplay, the additions of camo and the loss of radar added significantly to my enjoyment, despite my dreading the loss of the latter prior to playing. It turned out that not having radar put me more into the game, where in MGS and MGS2 most of my play was like a minigame in this little box where it just happened to be acted out on the rest of the screen. I wasn't paying attention to Snake, or my surroundings, I was just watching this box and moving my little dot to avoid the yellow triangles. Without that, I had to actually watch what was going on, and keep tabs on the guards myself. Luckily the use of camo allowed you to get in close enough to see what was going on without being spotted right off the bat.

On a technical level, some of the game looked really nice, and some of it looked downright astonishing. The entire thing was done in real time, and I was left dumbfounded during certain scenes as to how they managed to squeeze this out of the ancient PS2 hardware. The scene towards the end which is now just reverently referred to as "the motorcycle sequence" is a joy to behold, both due to the technical ability on display and the way keeping it in real time, and thus keeping it interactive, immerses you in a fantastic action sequence.

That brings up the direction, which is almost unheard of in games. For the most part, even visually-heavy games have a very bland, plop- down-the-camera-and-point-it-at-the-thing style of direction (or more accurately, lack of direction). But here, one can actually see an artistic vision being put forth, and choices in blocking and camera movement coming from what the director wants to convey, rather than just what needs to be in the frame. I'd have to play again to be sure, but I think some of it was even made to simulate a handheld camera.

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, there was the story, which I expected nothing out of and got everything instead. It was involving, and had many twists and turns, but actually stayed cohesive and understandable throughout, and even managed to be genuinely touching at the end. Even rarer for games, there are a number of characters you actually enjoy watching, like you'd enjoy a good actor's performance, and you look forward to seeing them again. It's a demonstration of something that Hollywood still hasn't quite grasped: that you need to actually care about the people in the story for you to care about what's happening to them, no matter how many explosions are involved.

MGS3 also deserves very special note for another thing Hollywood hasn't managed: A fully realized, non-cliche middle aged woman as a main character.

7. NiGHTS into Dreams... (Saturn, 1996)

More flying. My preferences are trying to tell me something.

So many developers are afraid to stand out. They know they need to, so their game doesn't disappear in the crowd, and yet at the same time it can't be too radically different or they risk turning people off. At their best, Sega was never afraid to stand out.

NiGHTS (that's how the logo is spelled; who knows if that's how they actually intended people to type it, but I'm going with it) is a gorgeous game. It has a style that is not only unique and stands on its own, but enhances and melds with the theme of the game. If an androgynous purple harlequin flying through a myriad of landscapes filled with bouncing opera singers and psychedelic winged fish creatures doesn't say "dreamworld," I don't know what does.

The concept is admittedly a little simplistic. NiGHTS must fly through the stage collecting blue orbs and depositing them in a special container, and must gather and deposit enough before time runs out. There's more replay value than one might think, however, as you are graded for your score at the end of the stage, and you have to maximize your use of time in racking up points if you want to get the best grade. It becomes a bit like perfecting your line in a Tony Hawk level, long after you've completed the goals set out for you by the game.

Really, the main draw is just experience of the whole thing. There are some people who have been on a particular roller coaster or amusement park ride a thousand times and never get tired of it, and it's much the same here. It never gets old to take a break and revisit these trippy dreamscapes, swimming through the air and enjoying the view.

Games like NiGHTS and Jet Set Radio represent the kind of Sega I wish we'd see more of. They were the pinnacle of cool because they did their own thing and happened to be very good at it, not because they were trying to match someone else's idea of cool (see: Sonic and his ever- present legion of squealing '80s guitars).

6. Dark Cloud 2 (PS2, 2002)

I'm one of the few who enjoyed the original Dark Cloud. I really liked it. It wasn't perfect, but it was a solid early PS2 game with a lot of charm. However, if you ever need a lesson on how to do a sequel right, you only need to look as far as Dark Cloud 2.

As a matter of fact, keep a copy of the game around just in case you ever meet one of those "industry analyst" pricks who wants to claim that gaming is dying because of a deluge of sequels, so you can smack him with it. The so-called experts like to compare video game sequels to movie sequels, when there's a very important difference: Game sequels, more often than not, actually improve on the original. You're not going to see many movie sequels that fix the mistakes made in the first one (or try to do anything different, for that matter), but game developers will learn what worked and what didn't in their previous titles and make the appropriate changes in the new ones. Dark Cloud had a great concept -- a sort of Zelda meets Soul Blazer in 3D, exploring dungeons one moment and rebuilding towns the next -- but it needed refining. DC2 cut down the number of playable characters, cut down the number of gauges and made loss of weapon HP less devastating (weapons just break until repaired now, instead of breaking and never coming back). They upped the variety in the dungeons, added more story and better graphics, and fleshed out the game with an overflow of extras and sidequests. There's a whole other game worth of stuff to do outside the main quest, be it fishing in the many streams and lakes found in dungeons and towns, playing golf after clearing out a dungeon floor, taking pictures of anything and everything to register ideas in your notebook for use in recipies to invent new items and weapons, or earning special medals for each floor by completing a certain goal, like clearing the floor in under five minutes or without using any healing items.

If you're ever locked away and only allowed one game to play for the rest of your life, this may be your best contender. It would take a lifetime to do everything that can be done in this game.

5. Grim Fandango (Windows, 1998)

I could've put any of LucasArts' classic adventure games in here, like the Secret of Monkey Island, or Loom, or Maniac Mansion, or Sam and Max, but Grim Fandango is just a hair above the rest. If you can imagine it, Grim Fandango features a Chinatown plot in Casablanca settings all melded into the world of Mexican folklore -- specifically, the Land of the Dead. Why didn't I think of that.

According to tradition, the recently departed must make a four year journey through the land of the dead to reach their final resting place. Manny Calavera, the protagonist, acts as a sort of Grim Reaper/travel agent, both picking up the newly dead from the land of the living and attempting to sell them transportation of varying quality based on how good they were in life. One day, he manages to get the case of a woman who was a perfect saint, who should qualify for the highest-class package available, yet something isn't right. She's denied any transportation at all, and when Manny leaves the office to investigate, she figures she'd better start hoofing it. He returns to find her gone, and soon takes off after her, following her trail while continuing to try and discover what's going wrong at the Department of Death.

The story and presentation thereof are top notch. If there's any justice in the world, Grim will one day become a project for Pixar. It's perfect for them, both in terms of an imaginative story and in the fact that it really wouldn't work in live action (everyone's a walking skeleton, for starters). Grim is also definitely the funniest game ever made, beating out the tough competition put forth by fellow LucasArts adventures like the Secret of Monkey Island, with incredibly witty dialog given life by exceptional voice actors. If you ever meet one of those people who say Conker's Bad Fur Day is the funniest game ever made, beat the shit out of them and then set them straight. If you are one of those people, I'm on my way to your house right now.

My only word of advice: Play the game with a walkthrough. Don't feel bad about it. It'll be much easier that way and you'll have a lot more fun. Adventure games, especially from LucasArts, feature notoriously obtuse puzzles that really aren't worth the effort required to guess the answers. Grim actually isn't as bad as some, so try it on your own if you like, but there are still some spots that just don't make a lot of sense.

4. Super Mario 64 (N64, 1996)

Shigeru Miyamoto is really taken for granted at this point, but occasionally one has to step back and remember just how much of a genius the man is.

Mario 64 was a great game. Everyone knows that. I don't need to point it out to anyone. But what is often forgotten is how untested a lot of the water was at the time it came out. 3D platformers, in such abundance now, were more or less unheard of except for the likes of Jumping Flash!, which isn't quite the same thing. The conversion from 2D to 3D was also a big question mark, and no one was sure whether a game could make the jump at all. Later games like Sonic Adventure proved that it took quite a bit of skill to do properly, otherwise things felt a bit.. off. On top of all this, the N64 was to use a new analog control scheme, one that hadn't been used on any console thus far (there were optional arcade sticks for older consoles, of course, but it was still a digital control pad signal being sent to the game).

And yet Mario 64 did it all, all within one game, and most shockingly, better than many games that have come out since. Few games to this day have managed to make analog control as fluid and intuitive as it was for Mario. The approach to platformers in this new dimension (with items to collect providing a brilliant solution to the question "where do you make the level start and stop when it's in 3D?") was so perfect that it was copied and continues to be copied by all other platform games. I'm not saying Mario 64 itself was perfect, because no game is. But few games have come as close. It was their first time picking up a bat, and they hit a home run. That doesn't happen by accident.

3. Final Fantasy VI (SNES, 1994)

There are few things rarer than getting exactly what you wish for, and then some.

Even at a very early time in my gaming career, I was looking to expand beyond the simple jump-and-shoot gameplay so common in the 8- and 16 -bit eras. I began to wonder why games couldn't tell stories -- real stories, not the shoestring "ninjas have kidnapped Ronald Reagan and we're busy and stuff so if you could go fetch him that'd be swell" plots covered in a paragraph at the front of the manual that developers hung their action scenes on. They could have characters you actually cared about and dialog scenes that actually entertained you instead of just providing a one-line explanation for why you were just fighting in a jungle but now you need to go to the arctic to fight some more. I wondered why they didn't make cartridges that were just stories, like interactive books that could last you for a long car ride or flight. I'm not sure how that would have worked out, though illustrated game novels were a moderately popular niche genre in Japan for a time.

I didn't know a lot about RPGs. I knew, thanks to my mother, that they were instruments of Satan that involved reciting magic incantations and calling upon demons to do your bidding. Not that I really bought that, but I knew she wouldn't let them in her house no matter what I thought, so I didn't bother to look into them too much. Besides, what little I saw of them was all numbers and stats and menus and looked boring as hell. Any articles or reviews about them focused almost entirely on what battle system the game used, the level of customization of the characters, and all the other mechanics of the genre that completely alienate anyone on the outside trying to understand.

Then one fateful day, I received the October 1994 issue of Game Players magazine, the one with Sonic and Knuckles on the cover, featuring Jeff "Lucky" Lundrigan's review of Final Fantasy VI. Well, they called it III at the time, of course, but nevermind. I read it, because I read every word of my magazines back then, and was absolutely stunned. I have to give credit to Jeff first and foremost, for opening up my mind to something I didn't know existed. For the first time that I had ever seen, the writer made no mention of the battle system. No mention of the number of spells or playable characters. Even the whole esper and relic systems were left out. In fact, he didn't talk about gameplay at all. He only wrote about the story. About the experience of living in this other world for 60+ hours, and all the little twists and turns within. Being as I am now, I would have eviscerated him for the number of spoilers he dished out, but at the time, I needed to hear it. I had to know it existed.

As I said, I was amazed. All those things that had been "wouldn't it be nice if"s in my head were there on the page. It immediately became my only desire to have this game. An agonizing number of months passed, each day of which spent rereading the article and spending minutes at a time looking at each picture, before Christmas finally arrived. I worked my best mojo (as if, oddly enough, a man possessed) to convince my mother that the game was no threat to the deep-rooted love of Christ she assumed I had. And all my efforts were rewarded when I opened up that one special gift on Christmas Day.

I don't think I can underemphasize the way FFVI changed my life. It served as an example of how much could be done with the medium. How games could affect you on an emotional level, beyond a simple adrenaline rush. How games could be not simply a distraction from the real world, but an escape. It featured the first game soundtrack I ever bought, purchased from the short-lived American store Square used to advertise on the back of the posters that came with their games. I ran out and played FFIV and Secret of Mana, and saved up all the money I had to pay the ridiculous $75 price tag on Chrono Trigger the day it came out, finding even more whole worlds that didn't just have great stories, or interesting characters, but were fun just to be in. It became the foundation of my beliefs about the importance of experience in games in addition to basic gameplay, beliefs which are evident throughout this list.

2. Planescape: Torment (Windows, 1999)

Planescape: Torment uses a terrible engine. The combat, particularly, is to be avoided. The visuals are not exceptional. The character modeling looks like a 15 year old boy's early experiments with Poser, particularly the females who all have the same huge breasts. Even the female zombies, for Chrissake.

This isn't the typical way of starting off a description of your second favorite game, but I say all that to underline this: Planescape: Torment has the greatest story in the history of video games, told through the best writing in the history of video games. This element is so strong (and, luckily, is also the main focus of the game) that despite any of its other problems, it still deserves to be considered one of the best games of all time.

Part of my enjoyment of the game was that I played it based soley on hearing how great it was, so I knew absolutely nothing about it going in. Not even really what the gameplay was like or how it looked. It was all fresh to me. So I hesitate to give much away. I'll just say that the story, or the beginning of it, anyway, is this: You wake up in a mortuary on a slab, but you're very much alive. Not that one would know by looking at you; you're covered from head to toe with cuts and scars, some fresh, some very old. You quickly come to realize that you can't remember why you're here, how you got here, or who you are. You don't remember anything. As you begin to do a little digging into your current situation, you also discover that you can't be killed. That if you die, you simply awaken again after a certain period of time. So you set out to discover more about yourself: who you are, and how you got this way.

There are two aspects to the experience that really knocks Torment out of the park. One is the story itself. It's extremely deep and involving, and yet never obtuse or overly complex. Unlike most game plots which concern finding the bomb or stopping the madman or what have you, the story in Torment revolves around a question: "What can change the nature of a man?" As one might imagine, it's somewhat rare to find a philosophical poser at the center of a video game, but that's what Torment is about. People, both our relationships with others and what it is within ourselves that makes us do what we do. Maybe it's not everyone's cup of tea (though everybody has an introspective moment now and again), but I found it fascinating to go along on the main character's journey of coming to grips with his past and himself.

Additionally, the world of the Planescape has been very well fleshed out, filled to the brim with tiny details you may never discover unless you play through several times. It's a universe with an infinite number of planes, basically different dimensions, where the world within that plane could be very much like our own, or completely different. There are planes where the inhabitants can shape matter with their will, and planes where laws and rules are not choices but factors of nature, governing a world of cogs and gears and precise synchronization. Planes with simple folk living inconsequential lives and planes with ancient demons fighting a war that has gone on for centuries. It's a setting that allows for a ton of creative freedom and room for playing different types of worlds and kinds of characters off each other, especially in the main town of Sigil where the game mostly takes place, a kind of hub where natives of many planes can be found.

The other aspect is the interactive side of the equation. One major hurdle in non-linear RPGs is that even though you're supposedly given the ability to choose what path to take, the choices can vary widely in quality from game to game. Often, it's a very dull binary approach where you're either good or bad. Your choices in conversation are either "yes, I'll bend over backwards to help you" or "no, I don't want to help, I'll just rob you instead." You're either a rosy-cheeked cherub spreading flowers and gumdrops throughout the land or a heartless killer who stabs people in the eyes because he likes to hear the squishing sound. Part of the reason for this, of course, is that for every different choice, there have to be different answers and new dialog and different events and a whole lot of extra work for the writers and programmers.

But Torment goes that extra mile. Every branch in the conversation has numerous choices, and not just the same couple of responses rephrased in different ways. Each choice has it's own subtle shade of difference. You can respond to someone with interest, or caution, or indignation, and they'll react appropriately. Moral decisions have shades of gray where you can still be a good person even if you've done something bad, depending on the reason you did it. Torment is the only game of this type where I can honestly say that there was always a dialog option that represented what I wanted to say in a given situation. It further increased my connection to the character and my emotional involvement in the story, as I was able to basically role-play as myself.

I'm sure I'll get yelled at by somebody for putting my number one choice above this game. And again, if the other aspects of Torment's design had been up to snuff, maybe things would be different. As it is, my top three favorites regularly switch places based on my mood at the time, so don't think of these as set in stone. But as it stands, as of this moment, I wanted something that had a more complete package. Which means..

1. Final Fantasy VII (PSX, 1997)

Remember when I said there were few things rarer than getting what you wish for? Well one of those things is getting what you wish for again, after hyping yourself up to the point where it seems you couldn't help but be let down.

Given that FFVI had become my favorite game of all time up to that point and had dominated my thoughts almost daily, it's fair to say I was a little excited about this one. I try not to let myself get my hopes up about anything, as that only leads to eventual disappointment, but I couldn't help it this time. I gathered up every issue of every magazine I had that contained even a bit of information on VII and read them and reread them every day. I recorded that Godawful Friday Night show NBC used to put on after Conan just because I knew commercials for VII would be on. I pre-ordered the game despite not even owning a Playstation, just to be sure I had a copy for myself. And somehow, after all this, it still managed to be more than I ever imagined.

FFVII was a source of great debate among many of the old-schoolers who felt that the game represented Square "selling out" or becoming more interested in making movie sequences than making a game. These are the same people who were lauding FFVI as the pinacle of Square's work, a game which features an entirely superfluous 15-minute opera scene. Actually, FFVII was simply a better realization of Square's potential, like moving from sock puppets to hand animation. They could finally show exactly what they wanted, where they wanted it, without having to reuse old sprites to save space and thus making every building, mountain and patch of grass look the same. With this new freedom, they created a vast world with a wide range of locations and styles and moods, from the gritty steampunk of Midgar to the oceanic natural formations of the Forgotten City. The world felt so much bigger just because each new area was so different from the last.

I should mention, by the way, that Midgar is one of the coolest fictional cities ever.

It's because of this greater creative palette that I place FFVII just slightly ahead of its predecessor. It was the style and depth of story that made FFVI so wonderful, but granted a purer form of expression by the removal of many technical limitations. I only wish that Square hadn't listened to the backlash against the more modern, less fantasy-oriented setting, as we could use more RPGs of Square caliber that break out of the traditional molds of swords and sorcery. Ironically now we have a lot of people complaining that Square doesn't change enough from game to game, so the lesson here is to never listen to fans. Ever.