|

P-boi's

Opening Day Ceremonies |

A friend and I had entered a lottery to purchase 4 tickets atop the Green Monster. It was the second year they had been around and ESPN voted them the best seats in baseball the year before. I guess the demand for them was so high that the normal first-come first-serve strategy used to sell the other seats wasn’t manageable. Sure enough my buddy won and was given an appointment to select the game he wanted to go to. Prior to his selection he redirected me to the information page they gave him. It said that Yankees games were subject to an altered price to be decided by the Red Sox. We fiddled with numbers for a while and arrived at a modest price we found completely reasonable to get Green Monster seats at a Yankees game. The day of his selection he called me: “You owe me thirty dollars.” Sure, I remembered what day it was, but I couldn’t figure out what thirty dollars had to do with anything. The stock price of the Monster seats were forty-five dollars a piece. Evidently the Red Sox decided that Yankees games were worth less than a game against Tampa Bay. Not only were we saving fifteen bucks a head, but he had managed to get the first Yankees game of the season. Mind you this was going to be only five months after Aaron Boone ended the ALCS in 2003. Upon hearing this I exclaimed “ohboyohboyohboyohboyohboy” all the way until the first pitch of the game whereupon I yelled “yaaaaaaaay”. The seats were, well, not seats. I guess the only tickets they had left were standing room only, which basically pins you back against a fence overhanging Lansdowne Street. The view, though slightly obstructed, was still breathtaking. At first I wasn’t so happy that there were thirty mile-per-hour winds whistling forty feet above a winter-like Boston, but it ended up coercing a well-dressed party to leave after just the top of the first. Their front row seats didn’t stay unfilled for long and I can honestly say I’ve never seen anything like it. I’ve sat directly behind home plate and also spent a few innings in the announcer’s booth and both pale in comparison. The crowd was electric before the first pitch was even thrown. It was the exact environment I had imagined. It gives you that feeling that at any moment you could hug a complete stranger while laughing wildly in joy. It didn’t take long for some fireworks to go off, either. Both Jason Giambi and Derek Jeter made errors in the first inning. After witnessing this I’m completely convinced that the seats we were sitting in were created solely to have a perfect view of a ball rolling right between Jeter’s legs. They should rename them “Jeter Seaters”. During the later middle innings a can of corn was hit in Manny’s direction (right below us). He wanders a couple of feet and haphazardly holds his glove up and proceeds to let the ball spit out of his mitt. The error proved not to be costly, but Manny still heard it from our section. The next inning while playing long toss with Johnny Damon he emphatically secured each catch with his right hand, each time turning around to show us that he was using two hands. Our section applauded his efforts. The Red Sox jumped to an early lead which they held for the remainder of game, winning six to two. The excitement and enthusiasm displayed within the ballpark carried right onto Yawkey Way and branched to the bars, T stops, and parking garages. I haven’t been around the world or even around the country, but there’s nowhere I’d rather be than in Boston after a win over the Yankees.

It’s safe to say that many of the things that I love came from the people that I loved as well. When I am with friends, I want to know what they like and why they like it. It makes me able to enjoy something else and opens up something new for me. I am, by no means, the type of person that will base all of my dislikes on the person I am closest to, however it would be wrong to say that their taste doesn’t influence me. The difference is that I can pick and choose instead of absorbing all that they love and no longer become myself really. Some of my favorite things I discovered and gained a love for through someone else. The more important the person, the more I wanted to share their interests so that I could be closer to them. My parents separated when I was in kindergarten, making me the second kid in my class to have parents that were getting divorced. The only other one was a boy named Matt who was held back a year and I remember as being a bit of a head case. I didn’t like being stuck as the only other kid without both parents. To make matters worse, I had an attachment to my father. He left us and I felt like I had done something wrong. I still will feel as though it’s my fault when something bad happens. When he did live with us the majority of his time in the home was spent in front of the television. It frustrated me both because I wasn’t able to watch what I wanted and because he seemed to pay more attention to sports events than his own family. The roar of the crowd over speakers would make me feel angry. That sound was my father ignoring me. To this day, if I watch any sport on TV, I turn the sound off. But now he was gone. The man who seemed to love me when he decided to give me some of his time rarely would see me. I would get sparse visitation days that ended up being awkward because I was a depressed little girl who missed my father but was upset at the same time that he was the one that left me. I wanted a relationship with him, but his life, his girlfriends, and his sports were more important. I was determined to have a relationship with the man who would buy himself Indians tickets and season tickets to see the Browns before he would pay child support for me and my sister. I decided that I would reach out to him since he did not seem to want to do that to me. I did it the only way I knew how: I started to pay attention and show an interest in baseball. For me, my knowledge of the sport began and ended what I knew about the old greats. I knew about Babe Ruth, who I referred to as “the Great Bambino” because I saw the Sandlot and thought I was cool. Everything else I had known was small facts. I knew nothing besides the basic understanding of the game. I was determined to learn more so that I could have something to share and to talk about with my father. In 1995, I asked to be taken to a baseball game for my birthday. I wanted to see Jacobs Field and watch the game with my father after I had started to learn more about the sport. He had taken me to a game at Municipal stadium a few years previous. I saw the Orioles play, but I don’t remember much about what had happened. We lost but I walked out of the stadium with a program, an Indians pencil, a wristband and a urinary tract infection. This time was going to be different. I was going to watch the game and know what was going on. I was going to be able to watch baseball and bond with my father. At the beginning of the season, my father ordered our tickets. I could pick to see the Indians play any team I wanted. I decided I wanted to see them play the White Sox. I was still learning about the players and thought that I should see Frank Thomas play. The local video store that sold baseball cards had a cardboard standup of him, so he had to be good, right? I made my choice and we had tickets for me, my father and grandfather for May 30th. To this day, going to a stadium to see a baseball game gets me excited. The first time entering Jacobs Field was much different for me though. When I had gone to Municipal Stadium, I remember it being dark with stained and practically crumbling concrete. Jacobs Field was open, clean and welcoming. I took this as a good sign as we went to our seats near right field. I sat and listened to my grandfather explain to me about the stats. I learned how a batting average was calculated and what an RBI was. My grandfather bought me a hot dog while my father watched the game through binoculars and talked with a few guys seated around us, ignoring me. I got to see Jim Thome hit a home run while I was once more ignored by my father. I was watching the team that went to the World Series that season as I realized that my father’s interests were more important to him than I was. So I sat and watch Manny Ramirez, Omar Vizquel, Kenny Lofton, Carlos Baerga and Albert Belle play the game. I sat and cheered as Eric Plunk was taken off of the mound as a relief pitcher and replaced with Jose Mesa. Since I didn’t have someone to enjoy the game with I sat and learned to appreciate the game on my own. When the game ended we drove away from Jacobs Field while the stadium lights were still on. The Indians had won and I had lost something. As they faded into the distance I sat and thought about what I had just seen. This time, instead of brooding over my failed attempt at bonding with my father, I sat and thought about the sights and smells of the ballpark and the team that I would follow throughout the season. That team became baseball to me that night. Seasons have past and my first thought when I think of a baseball team is the 1995 Cleveland Indians and all because of one night when I learned how to love a game because someone did not love me.

I was still saying something closer to "I'm-Oriole Stadium" when I first stepped into Baltimore's Memorial Stadium, the kind of stadium that gets lost between the Polo Grounds and the Astrodome and never shows up remembered fondly on Ken Burns' "Baseball." Buck O'Neil never smacks his lips and wistfully recounts the time ol' Satchel struck out 77 batters on a Maryland afternoon in Memorial. It's the kind of stadium that seems nice until it becomes suddenly inadequate, and sits there, not doing much, until someone's football team comes by and needs a home. "I'm-Oriole Stadium" made more sense, didn't it? They should change Miller Stadium to "THE BREWERS PLAYS HERE ARENA." Screw you, I was a baby. The first game I remember was in 1987, Orioles and Athletics. I was a few years into passionately collecting baseball cards, having just completed my 1985 Topps collection with some choice swap meet trades and a couple of flea markets. I wanted to see Cal Ripken, Jr. dive from second base to about third to catch a routine grounder, which is what I pictured as his natural state despite it happening once every few dozen SportsCenters. He dove and I wanted to see it. I also wanted to JOSE CANSECO. There is no verb there because what the hell do you do with a Jose Canseco? You cheered for him because you were seven, and he was good. The same reason I wanted a Bret Saberhagen rookie card so badly for like twenty minutes. They were going to be there, battling it out. Superstars. Classic Baseball Cards worth dozens of dollars. I got to Canseco. He was standing about ten feet from the third base line, hitting balls into a net. I was about three feet tall and pressed against the barrier, sandwiched like an errant little onion between the big slices of fat autograph hound, a few years before the Comic Book Guy and a few years after the maintenance of self-control. They screamed HO-ZAY! HO-ZAY! AUTOGRAPH HO-ZAY! HO-ZAY! I was told that I should address the players with respect, so I sat there blurting out a "Mister Canseco!" when I could. It didn't work. He just kept hitting balls into the net, pretending we weren't there. I could've reached out with my arm and touched him on the shoulder, but I didn't exist. None of us did. Him and the net. And a few other things, I guess. I tried to get to Ripken. He took batting practice, mulled around with Rick Dempsey or whoever, and went back into the dugout. I followed him around at about a forty foot radius wherever he went, trying to get close enough to the rail to let out a "Mr. Ripken!" Cal just kinda came and went. When I did get to the rail, someone heard me. Cal Ripken, Sr. walked up to me and complimented me on my Orioles hat, the old cool eighties one with the Oriole Bird cartoon on a white panel. He signed my program "CAL RIPKEN" and shook my hand. I told him that I loved his son. He said, "a lot of people do." I hopped back to my Dad and showed him the autograph. He was outraged. I had taken the pen and written "SR." in little block letters under the signature. My Dad was mad at me for a week. I thought it was necessary. I don't remember the score of the game. I recall the same senses that so many bring back about baseball. The smell of the sticky floors, the mustard, the green stains on white pant legs and the size of the stadium, the biggest thing I'd ever seen. I remember sunshine and clouds, little drops of rain, Eddie Murray's weird miniature afro-puffs to frame his ears. I remember players signing my program I can now only remember when I'm joking about old baseball cards and player names, or if I need a pun for The Dugout. It's lost in my memory somewhere pressed against the side of my head by the synapse versions of those card collecting fat guys, the memory of how a cheesesteak tastes or the first time I masturbated or something. There is one thing I remember, though, as clear as day.

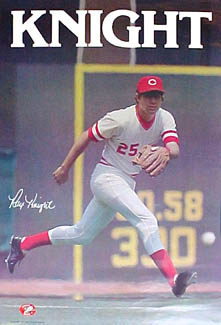

It's a joke. Ray Knight was an Oriole, for a while. He wasn't the best player on the team and he was never an impact player, but he was there, and he was walking out to take some swings. I was still there holding onto my glove and my marker waiting for Cal, or Jose, or Joe DiMaggio or whoever and he walked by. I shouted, "Mr. Knight!" He turned his head to look at me. I held up my program and said "Mr. Knight, could you sign my program please?" He took a few steps, looked back, and said, "Give me a minute, I'm going to take some swings and I'll be right back." That was it. He took some swings (they weren't great) as people started to crowd around me, arms outstretched, waiting to sell whatever autographs they got at flea markets on tables soaked with tobacco juice and homemade armor sweat. I pushed my knobby knees together and sat there waiting for Cal or Jesus Christ or Ken Gerhart to sign my program instead. The batting practice ended, and Ray Knight dropped his bat, took off his helmet, and walked directly to me without looking at another person in the stadium. He signed my program, softly said, "Thanks for waiting, sorry about that," and then walked into the dugout without signing another autograph. I thought about it a few years later when Rafael Palmeiro waltzed past a barricade full of baseball fans waiting after the game in the cold autumn winds to catch his autograph. "Raffi, Raffi!" we shouted. Some of us wanted to sell the signatures on the Dark Ages version of eBay. Some of us just really liked Raffi. He didn't make eye contact. He just walked to his car. Not a wave, not a nod, nothing. And we were left staring at Jose Canseco's back. Ripken stayed for an hour after that game, and the game so many years before, to sign autographs for anybody he could. I was a teenager. I was seven. And both times I stood at the top of the stadiums and looked down at the lines reaching off into the darkness or the warehouse, and I turned away. Cal was my hero. Cal is still my hero. I didn't want to wait for his back. Or maybe I was too afraid that I wouldn't get it. Maybe I just didn't want to wait in line. But I keep thinking that I headed home because it just didn't make sense to open up yourself to the fans like that and make sure each and every one of them goes home happy. Nobody else does it. Nobody else I was seeing, anyway. Ray Knight's autographed program sits in a box with the other things I've cherished and will never let go, and every time I get an autograph I think about his sincerity, and how much it meant to me. Jose Canseco wrote a book about how he was a cheater and was most recently on a reality show with Pepa and the black woman who looks like a vaginal Manute Bol from "The Apprentice." To this day I've never met Cal Ripken, Jr. I saw him hit two home runs against the Rangers, and I watched him dive from third base to about second to snag a routine ground ball. He threw a perfect strike to first base, and the first basemen, whoever he was, dropped the ball. It seems about right, doesn't it?

The tests came back negative. I wasn't even on the borderline. My mom felt like she was going to lose her mind, but in retrospect, I'm glad that I've been clinically proven to not have an imaginary disability that would've just put me on zombie drugs. Who knows what kind of boring person I'd grow up to be? I sure as hell would never have taken up writing as a hobby or a passion. So thanks a million for setting my mom straight, doctors. I'm eternally grateful. This has nothing to do with baseball. I just wanted to come up with some kind of explanation as to why the only things I remember about my very first baseball game was that it was my 7th birthday and...

I vaguely remember making fun of Juan Samuel's

name. I thought he was Chinese. Say it out loud & tell me I'm wrong.

At one point my dad got excited about something. Maybe Mike Schmidt

hit a home run. I saw Mike Schmidt play a game of baseball, & I

don't even remember it. Why not? No wonder the Phillie Phanatic tried to eat my face. Maybe it was the wake-up call I needed, because that game was the turning point of when I started wanting to take interest into what the hell was all over our walls. I started watching games with my dad. We'd sit in his room & share a big, yellow bucket of pretzel rods. There was a guy from St. Louis who could do a backflip. His jersey read number 1, & that's what he became for me. I'd go downstairs & make my dad's little Ozzie statuette do backflips onto the couch. I'd make Kirk Gibson trot around an imaginary diamond on the rug, even though I couldn't make him let go of the bat & throw his arms up in triumph. Roger Clemens's statuette was skinny & looked nothing like Roger Clemens. Well, I guess that's redundant. While I was down there, I studied the names & faces on the wall. I took pride in his collection whenever we'd have company over. They'd bask in awe at the scribbled signatures, & I understood why. I'd laugh whenever my dad answered the burning question, the same one they'd always ask... "How do you know that's really Mickey Mantle's signature?" Take that, fatty. By the time I was 15 & realized that I had the power of being a normal high school student who didn't pay attention because high school is fucking boring inside me all along, my younger brother & I had grown into the baseball fans I'm sure my dad had always secretly hoped for. So he decided that we were finally mature enough to appreciate a trip to Cooperstown that summer. By "mature," I mean as baseball fans, because even my dad, the almighty fuehrer of table manners, told our neighbor that a road trip with the men of the house meant one thing... "We can fart in the car & laugh about it." It was there, at the Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, or more specifically having lunch at a quaint little place down the street, where my dad revealed to us that he got us tickets to the All-Star game. It was in Philly that summer. I already knew that, but the big catch was that he only got two tickets... one for my brother, & one for me. We were going to a baseball game by ourselves. We had finally come of age. He dropped us off about a block away from the stadium, & we were on our own. Even better was that I had started working my first job that summer, as a life guard at a water park, so I actually had my own cash to spend on hot dogs & popcorn & soder pop & not a T-shirt because really, you can only have so many Phillies shirts. Somehow that number has been reduced to zero between then & now. We were seated behind the right field foul pole in the part where the upper deck hangs over you. Not great seats, but considering that Veterans Stadium was a shitty ballpark & had like 50 good seats in the entire place, they weren't terrible. We had a decent view of the entire infield. I was the grown-up of the group. I was happy. I lost a contact lens during the first inning & didn't have my case with me so I just put the fucker in my pocket until I got home. I was happy. Happy & half-squinting like Popeye. It was awesome. A drunk guy in the box seats ran over & slid into second. Ken Caminiti hit a home run like 30 feet to our right, & we all got to boo Joe Carter every time he did something or had his name mentioned because fuck Joe Carter. Philly fans are the most bitter, unforgiving sons of bitches on the face of the earth. And we were one with them that night. We could boo Joe Carter & laugh about it. It was just like farting in the car. It was the last time the National League won an All-Star game. Sometimes I feel like I'm some kind of jinx. I go to an All-Star game, & the National League doesn't win since. I was born in 1980, & the Phillies win their last & only World Series. Maybe they won't again until I die, or at least move. Please consider buying me a house in a warm climate before murdering me. But having the NL win, almost catching a home run, laughing at drunk guys sliding into second, booing Joe Carter, getting my face eaten by the Phanatic... none of that stuff contributed to why that is my favorite memory at a baseball game. Part of it was the fact that my brother & I were there by ourselves, but the main reason would turn my dad from a regular father figure into a bonafide hero in my eyes... My dad snuck into All-Star game. He comes early for everything. We were always at church like 20 minutes early & sitting there like idiots. He's got a parking spot waiting for us by like the 6th fucking inning. So when a crowd of impatient families were on their way out, he walks up to the gate & says he forgot something. What ticket taker is going to check your ticket by the bottom of the 6th? One such impatient family was previously seated right in front of us, so he took their spot, & we watched the final third of the game together. On our way out, they were giving out these big water jugs with the All-Star game logo on them... but only to people with some kind of voucher that came with the programs or whatever. I don't remember, but the point is we didn't have any. No problem for my dad. He just slyly gave the guy a reasonable amount of crap about how he left his whatever in the wherever, & the guy hands my dad a jug. "Hey!" my dad called out as he turned his back. "I had two!" That crafty son of a bitch. We spent the next few summers after that taking trips to other ballparks. Just my dad, my brother & me. We went to Baltimore & Boston, to Cleveland & to Shea. We farted in the car & laughed about it. But none of those games shine in my memory like the one at home, right across the river in Philly. It was a cast of All-Stars, but the only all-star I remember is my father. There are things I hate about the man. There are things everybody hates about their fathers. But by God, he snuck into the All-Star game, & I will always have a twinkle in my eye for him because of that. I may be the only person left in this house who admires him for his passion for the things he loves, particularly baseball, & for his crafty son of a bitchery. God, do I love my dad. He should be a double agent or something. One agency for each water jug.

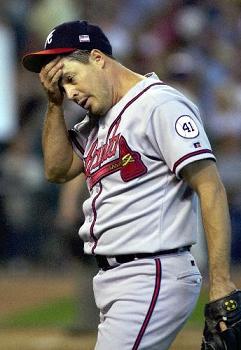

Look at any opening-day major-league roster this year. Chances are, it won't look anything like it did ten years ago. Maybe one franchise player is still hanging around. Maybe they were dominant, then were their division's whipping boys for a few years, then rose to respectability again. Maybe they've just stayed terrible. But the Braves, unlike almost every other team in the major leagues, have stayed good. Why? How? Their players have come and gone. But the players who step in to take their place keep it going, and they in turn pass the flag onto their successors, and so forth. The Braves are the "24" of major league baseball. That show has had around 67 directors of CTU. You watch an episode of the first season of the show, and then you watch an episode of the fifth season, and you feel like they made the first season in like 1988. You don't understand how they've been able to kill off all these beloved characters, and face down these threats of overwhelming magnitude, and remain in first place. But they do it. So there I sat, in, like, season 2 of "24", eating some cotton candy and watching Fred McGriff toss the ball around the infield. This was the second-to-last season the Braves would spend in Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium. By most accounts, a pretty ugly stadium; yet another sports complex built in the 60s and 70s that looked like a spaceship. But damn it, it was our spaceship, and it's kind of a shame to see parks like this go. We hold the Fenway Parks and Yankees Stadiums in such reverence, but can't manage to spare a fraction of that reverence for the Atlanta Fulton-County Stadiums or Riverfront Stadiums. Why not? Spectacular things and unforgettable moments have happened in these stadiums as well. They just don't happen to agree with our cultural aesthetic tastes at the moment. I bet when they were building Riverfront Stadium, they scoffed at Crosley Field. Then they laughed at Riverfront Stadium when they built the Great American Ballpark. In about thirty years (since we know structures only last about thirty unrefrigerated years before they start growing mold anyway), they'll tear the Great American Ballpark down to build a field that looks like, say, a giant scorpion holding a machine gun. We've still got about fifteen years before baseball pundits start waxing poetic on these sorts of stadiums, so I'll try to beat them to the punch. My favorite part of that entire ballpark was the baseball with the "715" on it painted above left-center field. When the game hadn't started yet, and there was nothing on the Jumbotron to watch, that was what you looked at. I'd trace the path from home plate to that "715" with my eyes, and then back. The first giant stake of American home-run history had been driven into the ground by Babe Ruth. And the second was right here. There was no grassy knoll peppered with busts and plaques. There was only a bunch of asphalt and cars, and a giant Southern metropolis beyond that, and a bunch of guys with mullets and WCW foam-and-mesh hats selling boiled peanuts beyond that. By common standards, not romantic at all. The general assumption, even after all this time, seemed to be that baseball belonged to New York and Boston and Chicago, and that places like Atlanta were just sort of borrowing it for a while. But whenever you started thinking that, you only had to look up at Henry Aaron's giant "715", and you'd know that baseball was here just as much as it ever was anywhere else. That day, in a stadium that no longer exists, we hosted the Montreal Expos, a team which no longer exists. The game was postponed a full fifteen minutes because the ground crew couldn't manage to chase off a Dodo bird which had found its way onto the field. The Braves won, 5-4, in ten innings. As I recall, Marquis Grissom won the game with a headfirst slide at home. We were about twenty games up in the division with about five games left to play. This game carried no mathematical significance. My friend and my brother and I, and 40,000 more, yelled until our voices went scratchy. The first pitch that day was to be thrown by a young Braves fan who had been diagnosed with cancer. He succumbed to it about a week before he was to throw it. His parents asked Greg Maddux, his favorite player, if he would throw the first pitch in his place. Maddux accepted. We watched as he walked to the mound. It goes without saying that Greg Maddux will be in the Hall of Fame soon after he decides to stop playing. He's an unbelievable player to watch, whether he's 29 or 39, but during the mid-90s there was absolutely nobody like him. He belonged to that very small group of athletes, with maybe Michael Jordan and Muhammed Ali and Barry Sanders, who could do something to make you stand and clap, even if you were watching him on TV by yourself. He was, and is, possibly my favorite baseball player. He reached the mound, gave Javy Lopez a look, and threw a 60 MPH perfect strike. The crowd, educated of the situation from the Jumbotron, roared. Maddux stood there an extra second, and walked back to the mound. I watched him closely. He rubbed his hand across his face. He was clearly beginning to cry. Moments later, he walked back onto the mound, allowed two runs in seven innings, and earned the win.

|

|