Seven Hill City

by B. Thompson Stroud

Chapter 20

Yesterday Auburn asked me in her own way if I regretted

any of the things that happened with Aranea. She was lying on the floor with her legs up,

holding them at almost a right angle, and I like to think she struck that pose to soften

the blow of what she had to ask. I don't know what to say. I know she worries about Aranea

sometimes, usually when she's being obvious. She'll start fidgeting with her feet or

resting her head on parts of me she normally doesn't use to rest, and I'll know that she's

trying to come up with the appropriate quote to fish for what she wants me to say. She

wants me to say I always preferred her. She wants me to say that she's the only girl I've

ever wanted to kiss, hold, or powerslam onto furniture. I don't know what to say.

There have been moments from the very beginning where I doubted and regretted the things I

did, or said, or felt. Even after I realized how much more necessary the true love and

appreciation of friendship is there were still times where I wanted to grab her around the

waist and kiss her, right there below her bellybutton, right there where it would make her

laugh and I'd be close enough to feel her insides move. I think of it now. I'm not

confused about what she was. I'm not confused about what she meant to me, and what she was

supposed to mean. But even when you erase the message from the board there is a faded

script that remains. It's not a complicated message. It doesn't make me want to die,

anymore. I can't lie and say I don't see it.

I can remember the first time I learned about regret, in what old people refer to as

"the hard way," which probably should've involved bloodshed and dragging my best

friend across a jungle to keep bombs from exploding on his face. My first brush with

regret was "The Smurfs." There's no message here about commercialization or the

emptiness of nostalgia...I was just happy to see them, live, walking around in front of

me.

Before the movie studio bought up the old amusement park it was run by cartoon people. Not

cartoon people; people who made cartoons. If they make weight distribution mistakes they

end up with hospital time, not giant pancake hands. They made the rides and attractions

revolve around their characters and creations. What would eventually become a "pirate

cave" belonged to a thieving bear. The kiddie-coaster was mystery-dog themed. And

long before teenagers danced in formation to today's best pop hits, teenagers slid into

foam suits and pretended they were three-inch tall blue people that lived in the woods.

They weren't three-inches tall, of course. They were huge. Blue foam midsections stretched

five, six feet into the air. Padded cardboard shoes painted white and tromped in; googly

pupils dancing pointlessly in open white eyeballs.

To me they were magnificent monsters. I was six years old. I knew nothing of death besides

the rightful ending place of the righteous and the damned. I knew nothing of murder or

rape, of molestation and tear-soaked underwear. I knew my father, seated in a Members Only

jacket and Orioles cap to my right, and the wooden bleachers warmed in the autumn by the

jeans and bounces of what I remember as hundreds of children, of which at least six or

seven I can remember. The blue men walked in circles and sang prerecorded songs about

friendship and the value of working together. They handed each other flowers and wide

green garden tools. They laughed without moving their faces. And eventually the man who

wanted to eat them, the man who gave them their only feasible life problems, came around

the corner of the stage, dressed in his own engorged plush head, ready to stomp and taunt

and shout.

I don't remember how good triumphed. The smell of funnel cake. The prickly feeling of

splintered wood on my fingertips. The sound of tennis shoes bopping against concrete.

Children's voices. Trumpet music and walking, walking. When Gargamel was defeated (he fell

down, and lay motionless) the Smurfs, their leader in red, asked delightfully, "Who

wants to come up on stage and dance with us?" The kids hovered from their seats

single-file like playing cards, one image and chocolate-stained face falling forward and

folding into the next. They laughed and cheered and made their way up to shake hands and

hug. One girl held hands with Papa, right in left and left in right, hopping in a circle.

My father leaned to me and asked, "Do you wanna go up?"

"No."

And now there is this hole in my memory, and all I can see is a birds-eye view of the

amphitheater, these empty semicircles escaping like an echo from the hysterical mass of

the stage. They are barren; slats of wood still vibrating, and there I am, beside my

father, staring blankly and making no sounds. I saw and knew only seconds later that I

should have joined in on the fun and danced like everyone else. I didn't know how to tell

my Dad that I wanted to, now. I want to run, I want to hug and be a satiated child and

experience these inconsequential moments that I will fucking forget in two weeks. But I

couldn't. My feet kept slipping out of Indian style, and I'm there now by myself on the

bench, miles away, trying to keep my knees from shaking.

Sometimes I think of this as I'm gagging, because, like an actor, it's easier to go

through the motions if you can identify with the feeling. On a Saturday afternoon I'll be

knelt over the toilet, resting my weight entirely on the ball of my hand, sending a

burning pain up my wrist and into my chest that I can't avoid for fear of breaking my

rhythm. The noises and the music are drowned there in the chilled water by the sounds I

make. On television it's a melodramatic "hoooooy!" Most of the time it's a gasp,

a bark. The sound you make swatting away someone's hand.

Scratch, scratch, scratch.

The eyesockets are the first thing to clench. I was once terrified that pressure on my

face could pop my eyes. So I pinch my eyelids shut, so I can't see the red and purple

lines creeping towards the center, and smell the fresh potpourri inches away in a basket

just above me. There are rocks of kitty litter jabbing into my palm. It's often like this,

and I can remember.

Scratch, scratch, scratch.

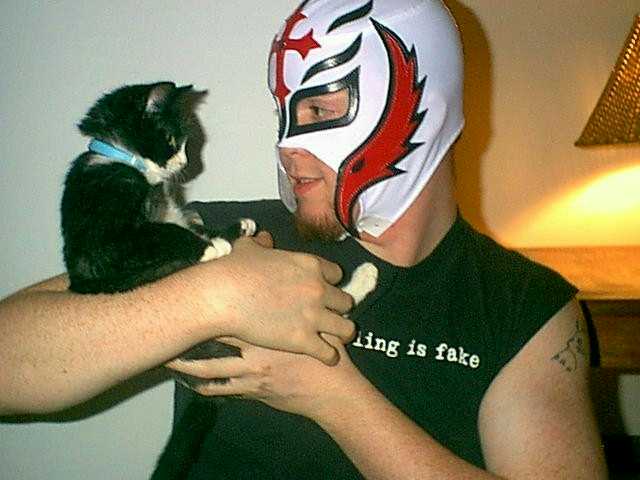

Before it comes I looked to my right to see my cat, two months old and black, pawing at

the walls of her box. The walls are a cold, solid plastic and filled along the bottom with

granite-like rivulets of green and grey. It is a singularly striking vision of normalcy,

framing this inexplicable frailty. I feel as if I move incorrectly the air displaced with

pin her and crush her. She's almost nine years old. But when I look at her I see her as

two months old, I see her as two weeks old lying on my front porch. I see her peeking up

at me from the side of the bathtub. I see her this way when I breathe, and when I close my

eyes. I don't want her to see me like this, ever, so I scoop her up and place her outside.

The door shuts.

Scratch. I can't remember what tense she's in. Scratch. Now, or before? Scratch.

I wanted a dog or a cat when I was small, but my only interaction with pets is the time

when the Dane bit through a three-year old hand to keep a piece of garbage from under the

porch from being pulled away. It was a scratch, but if I look correctly I can see the

holes in my hand still, the stigmata right in the center. It bleeds sometimes. And then,

at other times, it really bleeds.

The dog was out of the question. So was the cat. The goldfish died in a week. I can't

remember what I named them. Ricky and Robert, probably. They ate up and turned brown, and

floated. He's not responsible. He's too young. He learned to talk at seven months old. He

learned to read and write before he was two. He can't keep the thing that barely moves

moving. They die. The dog will die. The cat will die. He won't be able to understand. He

won't be able to take it.

So on a Thursday afternoon there was a hamster waiting for me in a clear, plastic cage

with clear, red plastic trimming. Chipped pieces of scented wood poked him in the sides as

he lay sleeping in a ball, his foot almost up his nose. He was adorable. He was mine. He

would prove to them that I was capable, and though I could never love him like a cat or a

dog I would make him work. Within five minutes I loved him like a cat or a dog. The

hamster will die. But I don't know it. I do, but I don't know it.

I was a little goofy moron and named him "M.C.," because if held under the front

legs his hind legs would stumble and slip on the long fur. It looked like he was dancing.

I thought it was funny, and I loved him. I took a dozen pictures with disposable cameras

that would never be developed of me holding him on my engorged belly. M.C. dangling from

my pudgy hands. M.C. sticking his little claws into my fat face to walk. He never did much

other than walk in whatever direction I pointed him. It felt like we were cosmically meant

to be.

I took him to school in the sixth grade. It was a "show and tell" exercise,

because our progressive teacher felt like we were missing some of the finer points of

Kindergarten. It was like the time I got excited reading about "Batman Returns"

news in the latest comic book magazine and asked to get up in class to read it to

everyone, even though nobody cared. When Billy would bring nunchucks and Sally would bring

a green rock I would bring my little buddy, this little rodent who made my life seem a

little bit better. By now his cage was huge, with blue and green and yellow tunnels

leading up and around, up and around to a lookout point, and then back down to his wheel,

his water, his dug-out bungalo. I held him beneath his arms and he danced over the long

fur, and the class laughed.

As I was leaving school that afternoon I carried the cage, M.C. inside, up and towards the

front Middle School doors. Before I could maneuver a way to push open the latch a pair of

eighth graders pushed ahead of me and sent me crashing to the ground. I remember staring

at a door hinge and hearing hard plastic hit metal and cement. I knew he was dead. I began

to scream. A thousand children, or at least a few, stood encircled around me as I grabbed

at the door and felt my heart climb up from my chest and fall out of my face. I wanted to

break the ground and kill the Earth. A pretty eighth grade girl helped me up and lead me

to the office.

M.C. didn't die that day. The fall broke his foot, and as I watched my assistant principal

pat the hamster's bloody leg with a paper towel I continued to scream, hoping that my

eyeballs would finally explode and I'd never have to see any of them ever again.

A year later M.C. was two and a half, and just sat there, eyes open, staring out from the

side of his cage. He wasn't moving. His cage was on my parents' bedroom floor, because I'd

planned to clean the cage and needed to move him somewhere safe. And he wasn't moving.

Every few moments his back would rise, and he would flinch, but never move. I must have

sat there staring into his cage back at him for hours. Watching for his back to shake.

Every few minutes. Shake. Flinch. It was terrible, and I could feel death walking through

me. I knew death was there, waiting to put its hand on him. I knew death was kneeling

there trying to put its hand on me.

I picked M.C. up and took him downstairs, setting him down belly first on the kitchen

table. "Come on boy, come to me." He stared. "Come on M.C., please come to

me, come on." He stared. His back flinched. I stared. I picked him up and placed him

on top of the microwave, hoping stupidly that the heat would feel nice and he could start

moving. I had played "Maniac Mansion" for the Nintendo so I knew the dire

consequences of putting a hamster in the microwave, so I just let him walk on top.

"Come on, come to me, please. Please." Then I remembered that microwaves were

supposed to be radioactive and quickly moved him back to the table.

He was on his back. I didn't know what to do. I was crying, just barely, the cry of the

oncoming, the cry when you know this is just the beginning. I tilted his head back and

opened his mouth. "Oh God," I said, taking a small breath. I didn't want to blow

too hard. I didn't want to hurt him. So I pressed my lips against his teeth and blew as

softly as I could. M.C.'s chest expanded thousands of feet in an instant and I recoiled.

"Oh God," I said, unable to stop the things inside of me. "Oh God."

M.C. just laid there motionless. "Come to," I started to say, but resigned to my

knees on the kitchen floor.

Scratch, scratch, scratch. The kitten, the cat, walked down the steps.

"Can you fly?"

"Of course I can fly. They're wings, doy."

"Have you ever done it, before? Fly?"

"Not really. I mostly fall."

"Yeah."

The November wind began to pick up and push the leaves over and past our feet, there ten

feet apart in the park grass. Her hair was white again, like the first time, and for the

first time I start to notice the lines around her eyes and the tension of age in her

breath. She was two years younger than me. She was beautiful. But deep down I knew that

she would have a hundred more years to go if she wasn't only supposed to be there now, and

then.

Aranea had a hole in her wing. The edges were a damp purple and stained, and I knew how

much it hurt. For her, and for me.

"Maybe I can help you," I said, nervously fastening the bottom buttons of my

jacket.

"Help me? You've already helped me."

"With your wings. Your wing."

"Oh," she said, looking back at the purple feathers stuck out from the

white. She stretched out the wing and opened the hole, and stumbled back.

"I can help you fly."

"Heh," she laughs, snorting. "That's pretty

inspirational."

"I'm serious." For the first time. My hand extended out for her.

She held it, smiling.

"Just in case you send me off into space by accident, we should make sure to get

in our Charlotte's Web reference for the day," she laughed.

"Templeton the Rat," I said.

"There we go."

I began running back across the field with all of the power in my legs, pushing the body

that had always felt so heavy through the grass and the wind like a bullet. Aranea trailed

behind, laughing like she always did, pounding her feet down into the damp grass, making

sure to feel it all. As she began to lift up from the ground I held on to her hand as hard

as I could. I didn't know why. It was the right thing to do.

Within thirty yards my arm was above my head and Aranea followed along there, above me,

parallel to the ground. Her head was tilted back and her face was pointed towards the sky.

Her hair shot back in streaks and her wings, feathers, blood and all, followed suit.

"Let me go!" she shouted.

I never could.

I held her hand for ten more yards until the wind took her up and away from me. I stopped

to catch my breath. My heart was pounding. My lungs died, and I don't remember where God

let me breath from. Aranea flew up and around, where the wind would take her, against the

blue and grey even farther up above. I meant to ask her when she came back down what the

raindrops felt like, as few as they were, from there. I meant to ask her how it felt to be

unlike anyone else. I meant to ask her how she could even exist for me, and what the

treetops looked like. I watched her scream with joy and do circles before floating back

down over the hilltop and to the ground. I must've forgotten.

When I found her again, two-hundred feet away, she was on her hands and knees, breathing

heavily, and smiling. Her fingers were digging into the ground.

"How was it, I asked?"

She looked back at me, for what felt like the last time.

"The sky is neat...but the dirt is so much better."

The next day, she was gone.

Scratch.

Scratch.

Scra

The kitten, the cat, was lying on my living room floor

when I came home. She was only two weeks old. Almost nine. She never made noise. She only

meowed when I would open a can of food. But she was whining, almost shouting there on the

ground, on the carpet, waiting for me.

I didn't know what to do. I hadn't seen her face like this before. She was afraid of me.

Her eyes were open and her mouth was open. There was a drip of spit and blood down from

the center of her jaw. She didn't want me to touch her, but she didn't fight me when I

did. Her little body was heaving. She'd always breathed heavily, but then again there on

the floor I could feel the hand of death waiting to grab her from me, waiting to walk

through me, waiting to put its hand on me.

It won't leave me alone. It won't go away. Not even this time. Not even for her.

The rain was heavy that night and I had to carry her under my T-shirt to the car, so she

wouldn't get wet. She was bleeding and screaming and I didn't want her to get wet.

My mother had called the animal hospitals in town. Nowhere seemed to be open. But there

was one. They would let us in. So we began to drive. I remember the street lights blinking

yellow, like I'd never seen. Through the raindrops on the windshield the red lights looked

as though they'd fallen to the ground and shattered into a thousand pieces. The hum of the

car shook me. She wouldn't be quiet. She wouldn't silently scratch away to keep me from

puking and she wouldn't look up at me over the edge of the bathtub...she just cried.

I could smell her urine and her feces. I looked down at her and she looked up at me. She

cried. All I could see was the black and the white, the T-shirt and the blinking yellow

resonance across us all. She couldn't control it. I wasn't mad at her. I wanted to cry

with her. I wanted to open up and scream like I did for my Grandmother, like I did for

Curtis, like I did for M.C. and for Aranea. When I decided I shouldn't have to control my

emotions anymore and let loose, I realized I'd already been crying for twenty minutes.

We didn't know where the animal hospital was. The animal emergency room is one of those

things you drive by every day but don't commit to memory. It's just a building you'll

never need. "If it breaks I'll just buy a new one!" We thought it was the

hospital fifty yards from the grocery store. Timberlake Animal Hospital. A cozy white

building with cozy white steps, and guardrails, in the dark. My Mother sat in the car. I

held this dying love in my hands, pressed against my chest to keep her calm, as I beat on

the door. Nobody answered. I sat down on the steps, and laid her across my thighs. She

wanted to get free but couldn't make herself move. She laid there across my thighs. For a

moment, there in the darkness and the distant rain, I said my good-byes to her. I've never

told anyone.

It didn't matter how old she was. She could've been twenty. She was two weeks old and I'd

just found her a few days ago on my front porch. I saw her lying there alone. I walked up

to her and knelt. "Hey there, little one." Her brothers and sisters that I would

meet just ran. She walked towards me. She put her head down and pressed it into my foot.

She made and broke my heart that day, and every day after. And every day since. She didn't

deserve to be taken away like that. She loved me, and she was taken away. For no reason.

For no reason.

My Mother drove to a payphone to get directions, and we eventually found the right

hospital. They were nice people. A white guy in a white coat. What you would expect.

Posters with cartoon dogs and big bones with phrases on them, a bathroom with a frog

motif, helpful nurses who don't think there's anything seriously wrong but want to take a

closer look. Cat Fancy magazine. Six Polaroids of happy dogs thanking the doctors. I'm

glad the dogs were okay.

Aranea, who was gone now, stood across the street that night watching me outside on the

curb, in the subsiding rain, clawing at the dirt. I don't remember what I was thinking.

It's so hard to do that now. I remember trying to break the ground. To pull up the grass

and kill the Earth. I remember door hinges. I remember my Grandmother's cotton hair.

Sometimes I don't even remember that.

Aranea stood beside me, kneeling. "Hey there, little one." I lowered my head and

pressed it into her foot. Her hands wanted to reach out and touch me, to make me feel

better. I know she was there with me. She couldn't press her fingers to my shoulder or

headbutt me in the chest, and I couldn't hear her snort, but I know she was there. She had

to be. I had to finally do it on my own. No excuses. No puke. No sex. No violence. No

love. I just had to sit there in the grass and take it. Without the melodrama.

And it hurt.

Then, every day after, and every day since.

It's hard for me to put into words how I feel about regret, and if I regret what happened

with Aranea. In the moments you can't relive there are feelings you will never feel again.

The feel of your father's jacket. The warmth of the bench. Adolescence built up around a

hamster, and learning how to love. The love of a kitten. Love. And Aranea, and Aranea, and

Aranea.

I love you, Auburn. No matter what I say. You have my foot, you have my fat face, and you

have my heart. And I hope you never regret.

For Shelton. Every day after, and every day since.